Om uppslagsverk, förläggare och litterära priser

Uppslagsverk hör till de allra billigaste böckerna man kan komma över numera på loppmarknader och i andrahandsaffärer, om de alls förekommer där längre: de är hart när osäljbara. För Nationalencyklopedin i tjugo band, i den näst dyraste versionen med ryggar i blått och guld, betalade jag för en tid sedan några hundra kronor. När den var ny och jag hade vaga planer på att investera i den kostade den flera tusen. Men till vad nytta numera, cui bono, när allt finns utlagt på nätet? Det samma gäller de flesta verk jag skrev en sammanfattande artikel om för Encyklopedia of Contemporary Scandinavian Culture, den som aldrig blev tryckt.

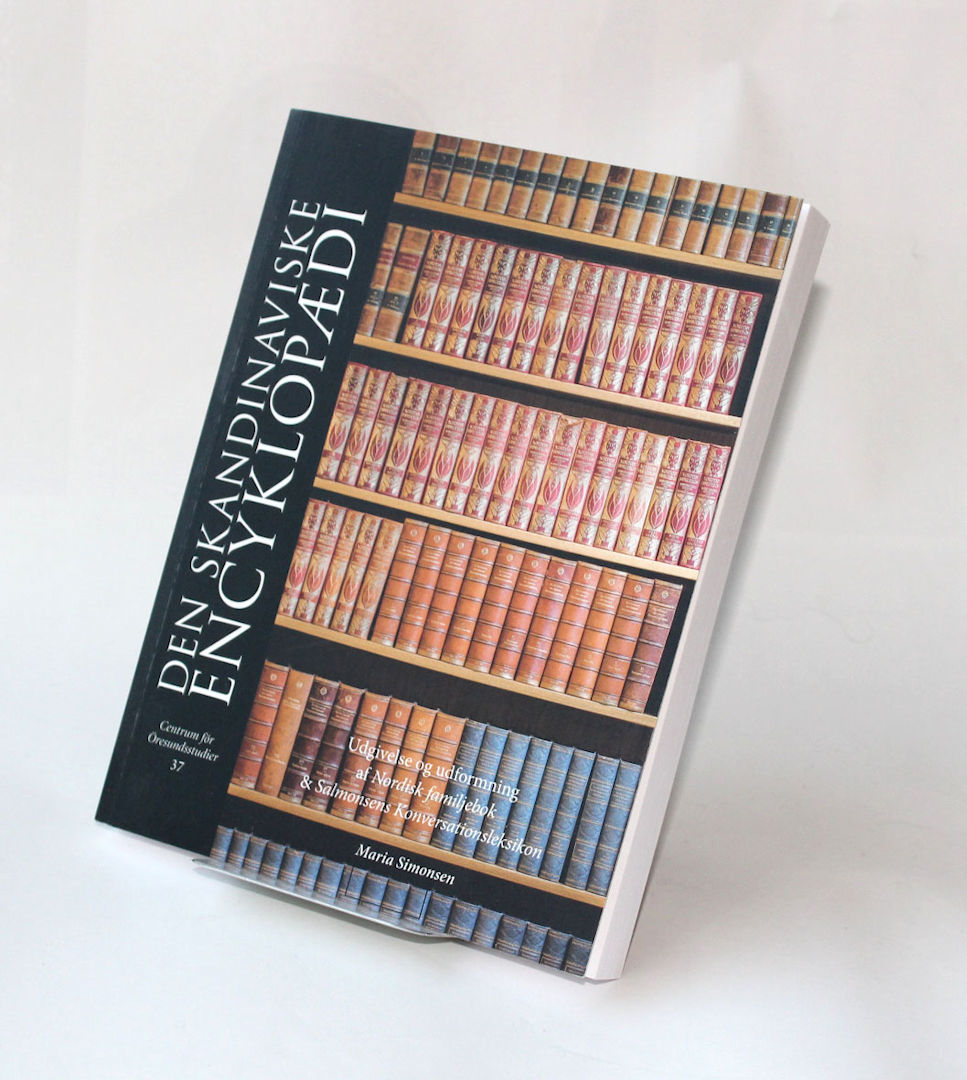

Sedan dess har kommit Maria Simonsens intressanta jämförande redogörelse för två av de genom tiderna dominerande uppslagsverken i Sverige och Danmark, Den skandinaviske encyklopaedi. Udgivelse og udformning af Nordisk Familjebok og Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon (Makadam 2016, utgiven i samarbete med Centrum för Öresundsstudier vid Lunds Universitet).

SBL, Svensk biografiskt lexikon, tuffar på för att komma till slutet: den började ges ut 1917, med den första artikeln om trädgårdsarkitekten och pomologen Rudolf Abelin (1864-1961) som skapade Norrvikens trädgårdar vid Båstad och som också var verksam på Adelsnäs i Östergötland – hans korta böcker om trädgårdsskötsel är eftersökta, och dyra. Konståkaren Ulrich Salchow (1877-1949) är den hittills senaste personen som är biograferad. Han fanns med i Allers samlarserie över idrottsstjärnor i början av femtiotalet där jag grundlade ett visst vetande om sådant folk.

När man tröttnar på att finna fakta i uppslagsverk kan man koppla av med tre parodiska skifter på genren av den alltför tidigt bortgångne Axel Wallengren (1865-1896), utgivna under hans pseudonym Falstaff, fakir: En hvar sin egen professor från 1894 och En hvar sin egen gentleman från samma år, och Lyckans lexikon två år senare. Han myntade den efterföljansvärda devisen ”Mycket läsa gör dig klok/ därför läs varenda bok.”

Nordic Encyclopaedias

The Swedish Nationalencyklopedin (National Encyclopaedia), the Danish Den store danske encyklopædi (The big Danish encyclopaedia), the Norwegian Store norske leksikon (Big Norwegian Lexicon), and the Finnish Uppslagsverket Finland (The encyclopaedia Finland) can all be found on the internet.

The first edition of Nordisk Familjebok ), the most monumental of the Swedish encyclopaedias, appeared in 1876–1899 (20 vols.). The second edition (1904-1926, 38 vols.) is usually referred to as ‘Uggleupplagan’ (The Owl Edition) because of the art nouveau owl on the spines of the volumes and the sometimes obscure and esoteric erudition that characterises this edition. Even if outdated, its pseudo-scientific explanations still make enjoyable reading, as seen in its defintion of ‘kyss’ (kiss) in vol. 15, dated 1911:

“A kind of sucking muscular movement with the lips, used in order to express an emotion by way of pressing the lips against a living being or a thing.”

There then follows a very knowledgeable survey of the kiss throughout history.

Nordisk Familjebok was superseded by Svensk Uppslagsbok (1st ed. 1929–37, 30 vols.; 2nd ed. 1947–55, 32 vols.). Tage Erlander, the later Prime Minister of Sweden, was one of its editors. Focus (1958–60, 5 vols.) and Stora Focus (1987–90, 15 vols.) set a new trend with their emphasis on the visual. Bra Böckers lexikon (4th ed. 1991–96, 25 vols.), more popular and less incisive, had a large print run and was mainly sold via a book club. Nationalencyklopedin (1989–96, 20 vols.), with a dictionary, atlases and yearbooks appended, is the most ambitious of the modern Swedish encyclopaedias; there is also an online version.

The Danish equivalent is Den store danske encyklopædi (The big Danish encyclopaedia) (1994-2001, 20 vols.), published by Gyldendal, which replaced the classic Salmonsens konversationsleksikon (1st ed. 1893–1907, 18 vols.; 2nd ed. 1915–30, 26 vols.).

The Norwegian equivalent is Store norske leksikon (4th ed., 2005–2007, 16 vols.), published jointly by Gyldendal Norsk Forlag and Aschehoug. All three are accessible on the Internet in updated versions, inviting their readers to add their knowledge (though censored by a panel of experts).

Uppslagsverket Finland (The encyclopaedia Finland) (2nd ed. 2003–2007, 4 vols.) is also available both in print and on the Internet. These dinosaurs in print are soon likely to disappear, replaced by exclusively Internet-based up-to-date encyclopaedias.

Specifically biographical information can be found in Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (launched in 1917 and still in progress), Dansk biografisk leksikon (1st ed. 1887–1905, 19 vols.; 2nd ed. 1933–44, 27 vols.; 3rd ed. 1979–84, 16 vols.), Norsk biografisk leksikon (1st ed. 1921–83, 19 vols.; 2nd ed. 1999–2005, 10 vols.) and Biografiskt lexikon för Finland (4 vols., 2009–2011), partly based on the 10 vols. of the Finnish Suomen Kansallisbiografia. Most of them can now be consulted on the net, as can Wikipedia.

Further reading:

Brewer, A. M. (1988) Dictionaries, Encyclopedias, and Other Word-Related Books. Detroit, MI: Gale Research Co.

Om förlag

I Norden liksom om uppslagsverk och litterära priser skrev jag för några år sedan följande översikter för Encyklopaedia of Contemporary Scandinavian Culture, den som aldrig blev tryckt. En del uppgifter har hunnit bli inaktuella – att rätta dem överlåter jag åt läsaren. I fråga om bokutgivningen kunde något också ha sagts om Kulturrådets publiceringsstöd till böcker, ofta utgivna på mindre förlag, med stort läsvärde och angelägenhet men vars kommersiella framgång redan från början kan ifrågasättas. Om förlag och förläggare finns en uppsjö läsvärda böcker, både memoarer och historiker, bland annat Karl Otto Bonniers fem band “anteckningar ur gamla papper och ur minnet” Bonniers, en bokhandlarefamilj, vidare jubileumskrönikan Excelsior från 1987 när det förlaget fyllde 150 år, redigerad av Daniel Hjorth och Håkan Attius, och Per I. Gedins Litteraturens örtagårdsmästare. Karl Otto Bonnier och hans tid (2003). Samme författare vars mor Lena Gedin under lång tid var ledande litterär agent med ett mycket stort europeiskt kontaktnät har också berättat sina intressanta förläggarminnen framför allt från Wahlström & Widstrand i Förläggarliv (2012). Han var den som såg till att pocketböcker började ges ut I Sverige. Vidare Bo Petersons PAN på Riddarholmen, Norstedts 1910-1973, och den anglosaxiskt inriktade Georg Svenssons sympatiska memoarer Minnen och möten. Ett liv I bokens tjänst (1987). Han kallades med stor rätt “den ende Bonnier som hetat Svensson” och drog igång både Bonniers Litterära Magasin BLM och Panache-serien.

Publishers

Large-scale mergers across national borders and monopolization trends are characteristics of the Scandinavian book market in the 21st century. Among the dominant Swedish publishing firms, Norstedts is the oldest one still in operation, founded in 1823. Traditionally, it has specialized less in fiction than in non-fiction, especially in the field of law, but not so nowadays – it is a leading publisher of Swedish as well as translated fiction. Its owner is KF Media, a branch of Kooperativa Förbundet, the co-operative organization which has also had and still has a strong impact on other sectors of Swedish society.

A number of smaller independent publishers have been incorporated into Norstedts, one of them Tidens förlag, for years the preferred publisher of many leading politicians in the Social Democratic party when writing their memoirs. Another subsidiary is Rabén & Sjögren, since its start in the 1940s focussing with great success on literature for children and young adults. Pippi Longstocking, immediately an international bestseller, was among the first books on its list, and its author Astrid Lindgren was one of the firm´s directors. KF Media also owns the book chain Akademibokhandeln with its numerous book stores, and Bokus, a leader for internet book-buying.

Only slightly younger than Norstedts is Albert Bonniers förlag, an overtowering force in Swedish and international publishing. Its founder moved from Germany via Copenhagen to Stockholm, where he opened a bookshop and a print shop in 1837 which soon took the leading position it has held ever since. Translations have always been an important part of its publications on offer. Panache, a prestigious series of translated foreign fiction, started just after World War II and is still active, and BLM (Bonniers Litterära Magasin) was the leading literary periodical between 1932 and 2004. Bonniers publishes around one hundred titles per year. It owns the internet bookstore AdLibris and a sizeable part of Bokbörsen, an internet shop for second-hand books which started on a purely private initiative. Furthermore, it is the leading publisher of weeklies and monthly magazines in Sweden, like the Stockholm daily Dagens Nyheter and the evening paper Expressen.

Wahlström & Widstrand, established in 1884, is now part of Bonniers. Among its authors was the novelist Hjalmar Söderberg (1869-1941), who also happened to design its trade mark, an apple presumably signifying knowledge. Recently, Bonniers has made forays into the Scandinavian market by incorporating the Finnish-language house of Otava in Helsinki. Natur och Kultur, founded in 1922 by the entrepreneur Johan Hansson and later a foundation, has retained its strong specialization in philosophy and psychology, and in literary classics.

The group of medium-sized Swedish publishing firms is fairly large. Atlantis, founded in 1977 has a special niche for books on art, history and music as well as international classics (“Atlantis väljer ur världslitteraturen”). It is now owned by a cultural foundation in Helsinki, and some of its books appear simultaneously in Finland and in Sweden. Carlssons is still operated by its energetic founder Trygve Carlsson with his keen interest in non-fiction, Brombergs has had a remarkable number of Nobel prize laureates on their list, and the leftish Ordfront also publishes its own magazine. The crime writer Henning Mankell has been a very lucrative asset for that co-operative firm but has transferred his books to the smaller firm Leopard. Another extremely successful writer, Jan Guillou, has moved from Norstedts to Piratförlaget.

The national and international breakthrough of Scandinavian crime novels is a remarkable feature which has affected other genres negatively on the book-market – as a result, fewer titles of Swedish poetry are now published. The number of independent publishing firms, often with few employees, is considerable, among them the “underground” Bakhåll, Tranan with a focus on books from non-European countries, Nya Doxa specializing in philosophy, Ariel, Pequod, Makadam (mostly academic books, handsomely produced) and Ellerströms. Its founder Jonas Ellerström is a poet, a translator and a literary historian in his own right with a wide contact net among international poets, of benefit for his range of books.

The dominance of British and American novels in translation, long a salient feature in Sweden, is now less so. Smaller firms have lately felt a responsibility to take care of fields that are shamefully neglected or ignored by the bigger and strictly commercial firms: poetry in translation, essays, and literature from less dominating languages and cultures. Swedish state support on the book market has had a strong impact in the last few decades, with subsidies to the low-priced series En bok för alla, now defunct, guaranteed author royalties often linked to library loans, and a state fund for authors. A lowered VAT on books meant an increase in numbers sold, at least temporarily.

That younger generations are less keen readers does not seem to worry publishers, as yet. Print-on-demand is expanding, making possible small print-runs at minimal cost. Academic texts, especially within the humanities, are still traditionally printed, and the growth of E-books and sound books in Scandinavia has been slow. This is a field where academic text-books and specialized literature is expected to grow. The space allowed serious literary criticism on the cultural pages of daily newspaper has narrowed down, compensated by a rapid growth of qualified bloggers on the net, and the net-based buying and selling of second-hand books has seen a rapid expansion. The recent generational shift among publishers is also a marked feature.

The easiest way of getting an overview of what is being published in Sweden are the three issues of Svensk Bokhandel annually, informing about the complete Spring, Summer and Autumn books. As for Denmark, Gyldendalske Boghandel Nordisk Forlag, founded by Søren Gyldendal in 1770, is the main publisher, now owned by Carlsbergfonden. The extremely prolific novelist, short story writer and poet Klaus Rifbjerg has been one of its directors. Among its ten subsidiaries are the imprints Forum, Fremad, Hans Reitzel (one of the early publishers of Karen Blixen), Høst & Søn, Samleren and Rosinante. The later two often publish young writers, a remarkable number of which have a background in the creative writing courses at university.

The rights of Gyldendal´s Norwegian authors, foremost the quartet Ibsen, Björnson, Lie and Kielland and the Nobel laureates Knut Hamsun and Sigrid Undset, were transferred in 1925 to an independent entity in Oslo, Gyldendal Norsk Forlag which ever since has been the leading Norwegian publisher, along with its competitor Aschehoug. Among Gyldendal´s subsidiary firms are Dreyer, Tiden (like its Swedish counterpart with Social Democratic sympathies) and Pax. Oktoberforlaget has a preference for radical and critical books, like its Swedish counterpart Ordfront.

Finland´s market for books in the Swedish language has traditionally been evenly divided between Schildts and Söderströms who have joined forces recently. The number of Swedish-speaking small publishers in Finland is dwindling, narrowing down the chances of getting published, especially after the merger of the two dominating forces. On Iceland, with its 300,000 inhabitants and its strong literary tradition ever since the sagas of the 13th century, more books are published and read per head than anywhere else in the world, only equalled by the Faroe Islands. The main publishers in Reykjavik are Edda and Forlagid with its subsidiary Mál og menning.

Litterära priser

Uppståndelsen, också den internationella, är överväldigande stor när Svenska Akademiens ständige sekreterare på slaget 12 öppnar dörren i Börssalen och avslöjar vem som tilldelats årets Nobelpris i litteratur. Bland andra har Sven Christer Swahn och Helmer Lång skrivit om den långa raden av pristagare sedan 1901. Efter femtio år kan man läsa dokumentationen kring överläggningarna bland De Aderton (under de senaste åren har de ibland varit färre än så) om hur de kommit fram till ett beslut bland många möjliga kandidater. Så fort det efter femtio år är fritt fram att forska bland de anteckningarna redogör en kulturskribent I Svenska Dagbladet för det. Litteraturen om det priset är efter hand stor. Gustav Källstrands Andens olympiska spel: Nobelprisets historia (2021) är den senaste omfattande historiken om både det och de andra Nobelprisen.

Ett tillägg till litteraturlistan ovan om nordiska förlag ska göras: Pernille Stensgaards fascinerande keönika Selveste Gyldendal – en historie som kom 2020, året då förlaget fylde 250 år. Den tar dock sin början betydligt senare: “Denne historie begynder 1952, da den ukendte ostegrosseren Knud W. Jensen ankommer till Klareboderne som atypisk og ideolologisk hovedaktionær. Med sig bringer han et ungt hold med vennen Ole Wivel i spidsen. De trækker fine, småfallerede Gyldendal op af støvet och ud i lyset.” (Oste-Jensen är ännu mera känd som skaparen av konstmuseet Louisiana i Humlabæk).

Literary prizes

In his pioneering study of literary prizes in Sweden, Jerry Määttä maintains that while literary criticism plays a far lesser role in our century than in the previous one, literary prizes are becoming increasingly important both for the status of authors and their publishers, and for the advertising and selling of books. The marked growth in the number of prizes on the literary market (that the majority of prizes have been instigated since 1945 seems to be a universal trend, also in Scandinavia) is, according to the American James F. English as quoted by Määttä, “one of the great untold stories of modern cultural life (—) awards have become the most ubiquitous and awkwardly indispensable instrument of cultural transaction.” His observation that literary and cultural prizes make use of economic, cultural and journalistic capitals is summed up in Määttä´s formula pengar (money), prestige, publicitet.

Nordic literary prizes are a veritable cornucopia. There are at least one hundred and forty of them in Sweden alone, some sixty in Norway (“We drown in prizes”, according to an Oslo critic), and a score or more in Finland and in Denmark, statistics fluctuate but they seem to be on the increase. A few prizes tower high above the rest both in pecuniary value and prestige. The winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature receives 10,000,000 SEK (2013), after having been selected by a committee within the Swedish Academy. This is by far the most commented on and also the most debated and controversial of all literary prizes since its inception in 1901 (much has been written on its history, among them by Kjell Espmark, himself a member of the Academy). Like the other five Nobel prizes, it is awarded on December 10, the day of Alfred Nobel´s death in 1896.

Also very substantial (5,000,000 SEK) is the annual international ALMA-prize in memory of Astrid Lindgren, to authors and illustrators of children´s literature, established by the Swedish government in 2002. The Prestigious Hans Christian Andersen medal, a Danish prize for the same literary category, carries much honour but no money. The combined sum of Swedish prizes of different categories is about two thirds of a Nobel prize. Some thirty of them are above the 100,000 SEK level. The Swedish Academy, established in 1786, hands out 21 different literary prizes, one of them being Svenska Akademiens stora pris which is as old as the Academy itself. The Academy´s Nordic prize goes beyond national boundaries, as does the Nordic Council´s literature prize, valued at 350,000 SEK and 350,000 DKK respectively.

Second in generosity after the Swedish Academy among Swedish institutions and academies is Samfundet De nio, established in 1913 thanks to a sizeable donation in the will of Lotten von Kraemer, with 11 different prizes (its grand prize worth 250,000 SEK). Some have been recurring stipends to authors in need of support – one of them Vilhelm Ekelund for a not insignificant number of years. The centennial history of this nine-member society (half the number of the Swedish Academy) and its role as an important and influential player on the literary field has been written by Inge Jonsson, its president since 1988.

In addition to academies and institutions, literary societies, trade unions, local authorities and the media (publishers, the press, broadcasting) are behind many Nordic literary prizes. A very great number of them with widely varying prize sums are linked to authors, among the Swedish ones to Bellman, Kellgren, Tegnér, Fröding, Heidenstam, Selma Lagerlöf, Ivar Lo-Johansson, and in Finland, where Finlandia-priset is the most prestigious one, to Runeberg, Aleksis Kivi, Arvid Mörne and Edith Södergran. In Norway, where Brage-priset and Kritiker-priset are the two most important prizes, others commemorate Ibsen, Hamsun, Obstfelder, Tarjei Vesaas, and in Denmark, where The Laurels of the Booksellers prize is influential on the book market, a Holberg medal (in addition to the H. C. Andersen one) is handed out.

Other awards are linked to publishers, in Sweden Bonnier, in Denmark Gyldendal, or to newspapers like the Swedish Borås Tidning´s recent prize to first-time writers and the Danish Weekendavisen´s litteraturpris. Swedish radio has yearly prizes for poetry, novels and short stories. One prize above all others has a strong impact on the Swedish book market, August (i.e. Strindberg)-priset, founded by Svenska Förläggareföreningen (the Society of Swedish Publishers) in 1989 and handed out in good time for the Christmas book season. Its recipient can count on being an instant bestseller.

Literature:

Jerry Määttä: Pengar, prestige, publicitet. Litterära priser och utmärkelser i Sverige 1786-2009, in Samlaren 2010, pp. 233-271.

Kjell Espmark: The Nobel Prize in literature: a study of the criteria behind the choices. 1991.

Sture Allén & Kjell Espmark: The Nobel Prize in literature: an introduction. 2006.

Inge Jonsson: Samfundet De nio 1913-2013. Hundra år av stöd till svensk litteratur. 2013

Ivo Holmqvist